Beyond Labels: How Machines Learn to See With and Without Human Guidance

Beyond Labels: How Machines Learn to See With and Without Human Guidance

Have you ever watched a child learn to recognize objects? Initially, parents point and name things directly: "That's a cat", "This is an apple". But soon, the child learns independently, categorizing new objects without explicit instruction. This beautiful transition from guided to autonomous learning mirrors one of the most fascinating aspects of artificial intelligence: the spectrum of learning paradigms.

In the realm of computer vision, machines can learn in remarkably different ways—from the meticulously hand-labeled datasets of supervised learning to the autonomous pattern discovery of unsupervised approaches. Each method offers unique insights into both machine and human cognition, revealing different paths to visual understanding.

This journey through learning paradigms isn't just about technical approaches; it's about fundamental questions of knowledge acquisition. How much guidance do machines need? Can they discover meaningful patterns independently? What parallels exist between machine learning and human visual development?

Let's explore this landscape of learning paradigms and discover how each shapes the way machines perceive and understand our visual world.

The Spectrum of Learning: From Full Guidance to Complete Autonomy

Machine learning approaches in computer vision span a continuum from fully guided to completely autonomous:

Supervised → Semi-Supervised → Self-Supervised → Unsupervised → Reinforcement Learning

(Most Guided) ----------------------------------------> (Most Autonomous)

Each paradigm represents a different balance of human guidance and machine independence, with unique strengths and limitations. Let's begin our exploration with the most guided approach.

Supervised Learning: Learning from Human Teachers

Supervised learning is the most straightforward approach: humans provide labeled examples, and machines learn to recognize patterns that connect inputs to outputs. It's analogous to a teacher showing flashcards to a student, providing both the question (image) and the answer (label).

"Supervised learning is the computational equivalent of learning with a patient teacher who shows you examples and tells you the right answer every time."

The MNIST Dataset: A Classic Teaching Tool

To understand supervised learning in practice, let's start with the classic MNIST dataset—a collection of handwritten digits that has served as a training ground for image classification algorithms for decades.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, confusion_matrix

import seaborn as sns

import os

# Create directory for saving generated images

os.makedirs('images/blog/learning_paradigms', exist_ok=True)

# Load a subset of MNIST data (using a smaller subset to be CPU-friendly)

print("Loading MNIST data...")

X, y = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, return_X_y=True, as_frame=False, parser='auto')

X = X / 255.0 # Normalize pixel values

# Use only a subset of the data to keep it CPU-friendly

n_samples = 5000

X = X[:n_samples]

y = y[:n_samples]

# Split the data

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

print(f"Training on {X_train.shape[0]} samples, testing on {X_test.shape[0]} samples")

# Display a few examples

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

for i in range(10):

plt.subplot(2, 5, i+1)

plt.imshow(X_train[i].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"Label: {y_train[i]}")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/mnist_examples.png')

plt.close()

# Train a simple model (Logistic Regression is CPU-friendly)

print("Training logistic regression model...")

clf = LogisticRegression(max_iter=100, solver='saga', tol=0.1)

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

print(f"Accuracy: {accuracy:.4f}")

# Create confusion matrix

cm = confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred)

# Plot confusion matrix

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

sns.heatmap(cm, annot=True, fmt='d', cmap='Blues')

plt.xlabel('Predicted Labels')

plt.ylabel('True Labels')

plt.title('Confusion Matrix')

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/confusion_matrix.png')

plt.close()

# Show some predictions

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

for i in range(15):

plt.subplot(3, 5, i+1)

plt.imshow(X_test[i].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

pred = clf.predict([X_test[i]])[0]

true = y_test[i]

color = 'green' if pred == true else 'red'

plt.title(f"Pred: {pred}\nTrue: {true}", color=color)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/predictions.png')

plt.close()

In this example, we've loaded a subset of the MNIST dataset and displayed some sample images with their corresponding labels. Each image is a 28×28 pixel grayscale representation of a handwritten digit, and each comes with a label indicating which digit it represents (0-9).

This perfectly exemplifies supervised learning: the dataset provides both the input (image) and the expected output (digit label). Our algorithm's task is to learn the mapping between the visual patterns and their corresponding digits.

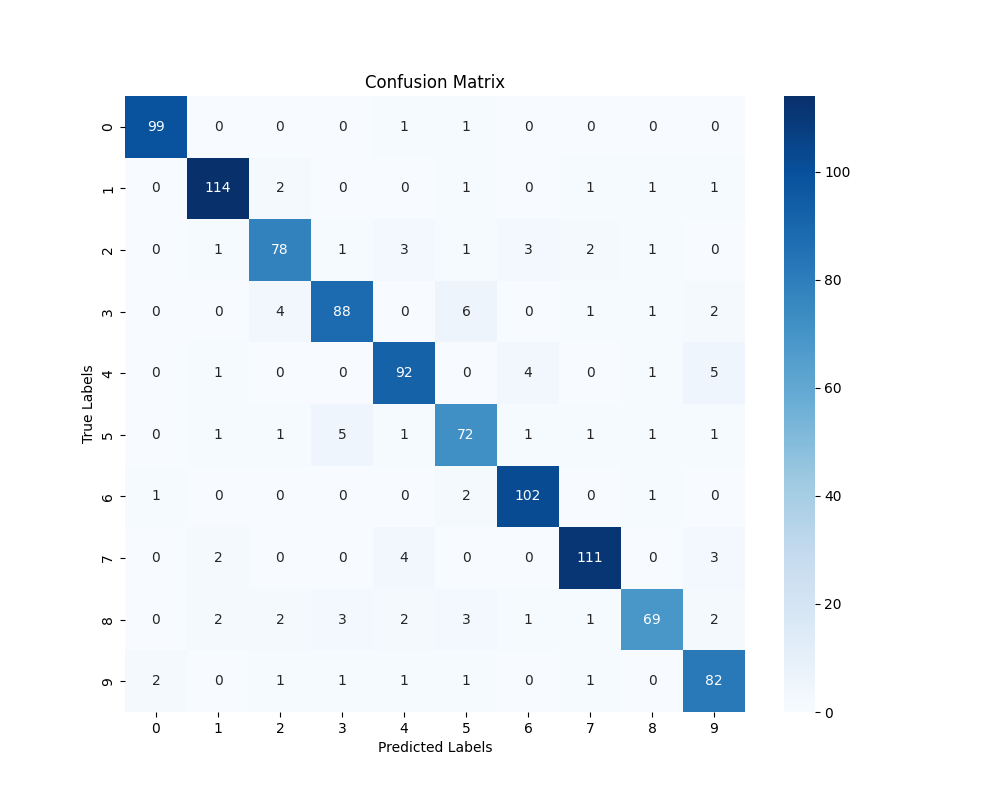

The confusion matrix above visualizes our model's performance. Each cell shows how many images of a true digit (rows) were classified as each predicted digit (columns). The diagonal represents correct classifications, while off-diagonal elements show errors. For example, we can see that the model occasionally confuses '4' with '9', which makes intuitive sense given their visual similarities.

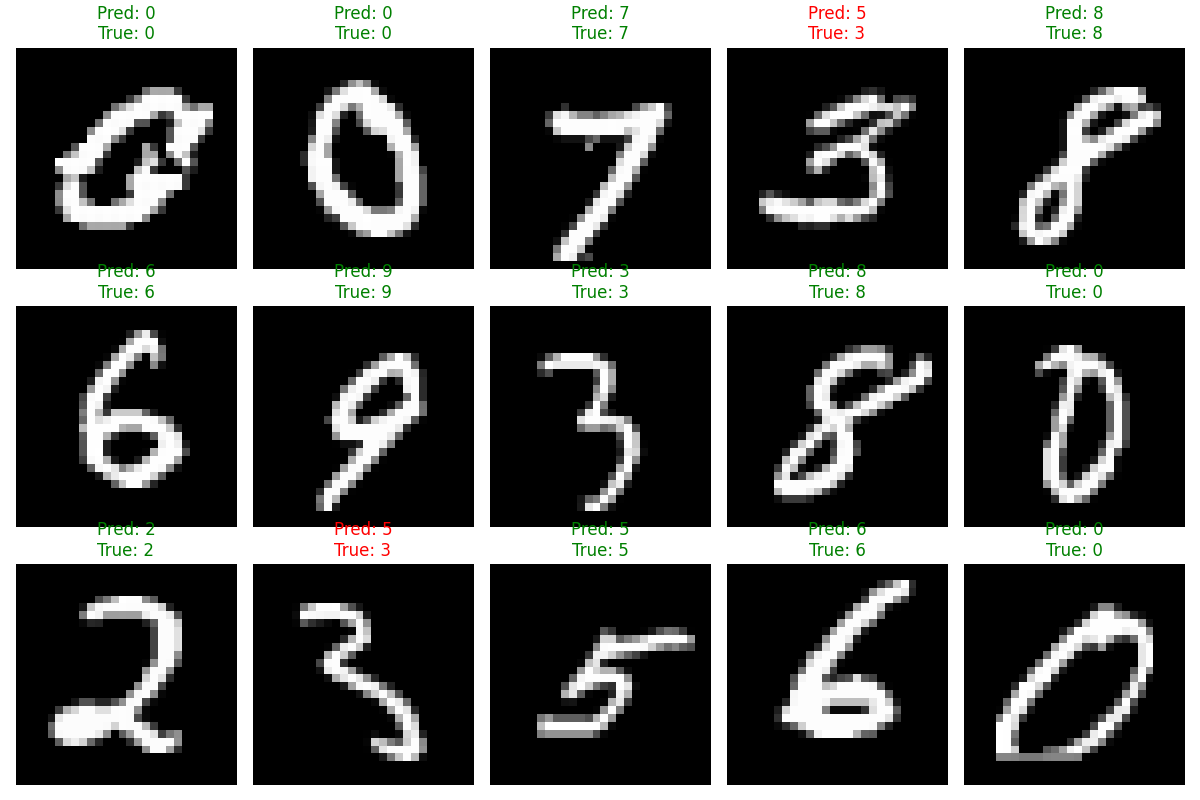

Here we see some test examples with both the true label and our model's prediction. Green titles indicate correct predictions, while red shows mistakes. Even with a relatively simple logistic regression model, we achieve good accuracy on this task.

The Power and Limitations of Supervision

Supervised learning excels when:

- We have a clear definition of what we're looking for

- We can provide many labeled examples

- The test data is similar to the training data

However, it faces significant challenges:

- Label dependency: Performance is only as good as your labels

- Data hunger: Requires large amounts of labeled data

- Generalization gap: Often struggles with novel scenarios

- Label bias: Models inherit biases present in the labeling process

These limitations have pushed researchers to explore less supervised approaches, which we'll examine next.

Unsupervised Learning: Finding Patterns Without Guidance

At the opposite end of the spectrum is unsupervised learning, where algorithms receive data without any labels. The goal shifts from mapping inputs to outputs to discovering inherent structure within the data itself. It's like giving a child a box of varied objects and watching them sort them based on their own observed similarities.

"Unsupervised learning is the computational equivalent of exploring a new territory without a map, where you must discover the landmarks and pathways yourself."

Clustering Images: Discovering Visual Categories

One of the most common unsupervised learning techniques is clustering. Let's see how we can use clustering to discover natural groupings in image data:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_olivetti_faces

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

import os

# Load the Olivetti faces dataset (small enough for CPU)

faces = fetch_olivetti_faces(shuffle=True)

X = faces.data

y = faces.target

print(f"Dataset shape: {X.shape}")

print(f"Number of unique individuals: {len(np.unique(y))}")

# Display some sample faces

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

for i in range(15):

plt.subplot(3, 5, i+1)

plt.imshow(X[i].reshape(64, 64), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"Person: {y[i]}")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/sample_faces.png')

plt.close()

# Apply dimensionality reduction for visualization

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

X_pca = pca.fit_transform(X)

# Apply K-means clustering (unsupervised)

n_clusters = 10 # We'll try to find 10 clusters

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=n_clusters, random_state=42, n_init=10)

clusters = kmeans.fit_predict(X)

# Visualize the clusters in 2D space

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

scatter = plt.scatter(X_pca[:, 0], X_pca[:, 1], c=clusters, cmap='viridis',

alpha=0.7, s=50, edgecolors='w')

centers = pca.transform(kmeans.cluster_centers_)

plt.scatter(centers[:, 0], centers[:, 1], c='red', s=200, alpha=0.5, marker='X')

plt.title('Face Images Clustered in 2D Space')

plt.xlabel('Principal Component 1')

plt.ylabel('Principal Component 2')

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Cluster')

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/face_clusters_2d.png')

plt.close()

# Display representative faces from each cluster

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 8))

for i in range(n_clusters):

cluster_examples = np.where(clusters == i)[0][:5] # Get first 5 examples from cluster

for j, idx in enumerate(cluster_examples[:min(5, len(cluster_examples))]):

plt.subplot(n_clusters, 5, i*5 + j + 1)

plt.imshow(X[idx].reshape(64, 64), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"C{i}: P{y[idx]}")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/cluster_representatives.png')

plt.close()

# Compare clusters with true identities

cluster_to_person = {}

for cluster in range(n_clusters):

cluster_samples = np.where(clusters == cluster)[0]

person_counts = np.bincount(y[cluster_samples])

main_person = np.argmax(person_counts)

purity = person_counts[main_person] / len(cluster_samples)

cluster_to_person[cluster] = (main_person, purity)

print(f"Cluster {cluster}: Mainly person {main_person} (purity: {purity:.2f})")

# Visualize cluster purity

clusters_list = list(range(n_clusters))

purities = [cluster_to_person[c][1] for c in clusters_list]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

bars = plt.bar(clusters_list, purities, color='skyblue')

plt.axhline(y=0.5, color='r', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

plt.xlabel('Cluster')

plt.ylabel('Purity (Ratio of Dominant Person)')

plt.title('How Well Do Clusters Capture Individual Identities?')

plt.ylim(0, 1.0)

plt.xticks(clusters_list)

# Add value labels to bars

for bar in bars:

height = bar.get_height()

plt.text(bar.get_x() + bar.get_width()/2., height + 0.02,

f'{height:.2f}', ha='center', va='bottom')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/cluster_purity.png')

plt.close()

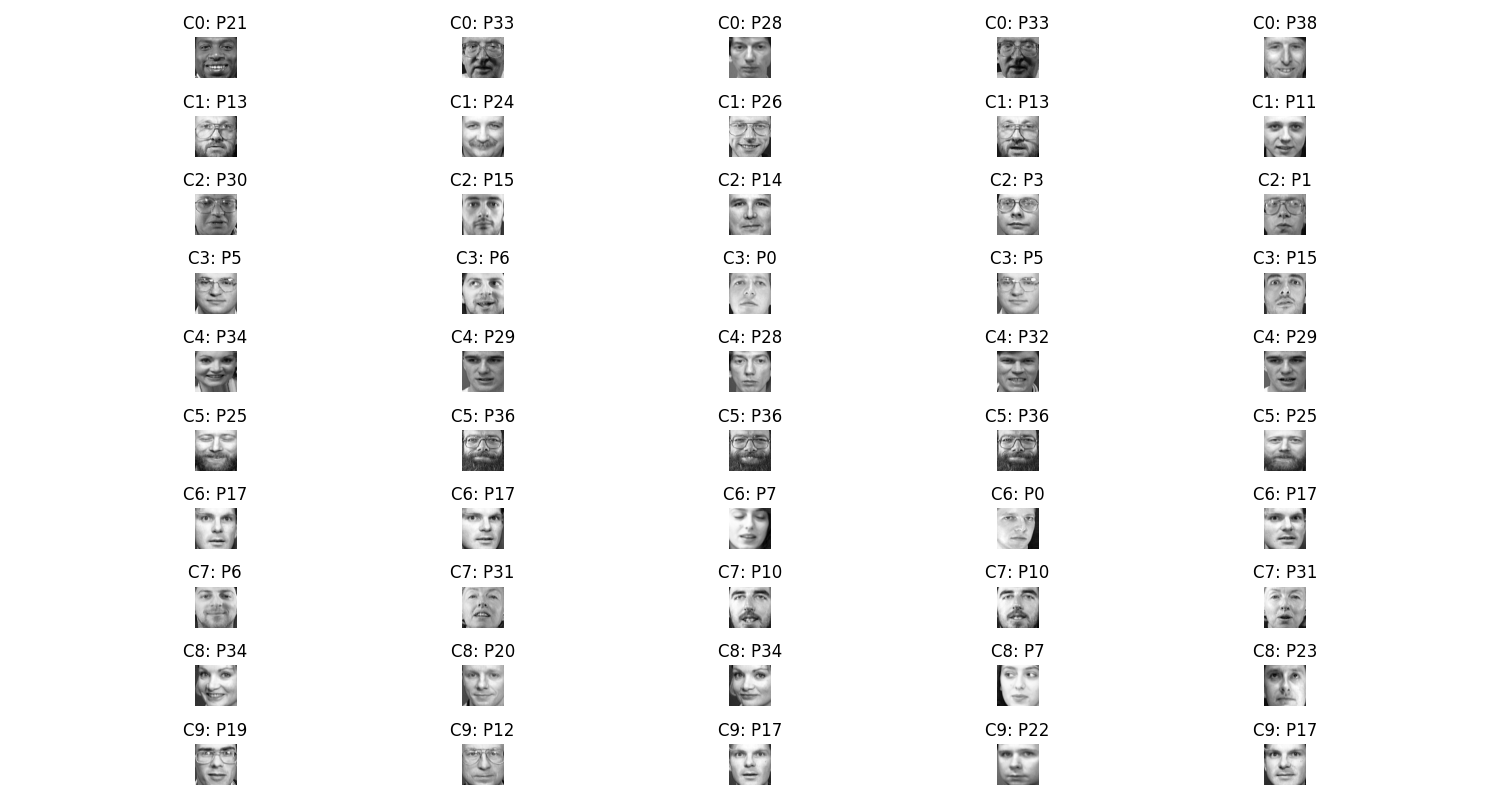

Here we see sample faces from the Olivetti dataset, which contains 400 images of 40 different individuals. Each image is 64×64 pixels in grayscale. Unlike MNIST, we're going to pretend we don't have the identity labels and see if our unsupervised algorithm can discover natural groupings.

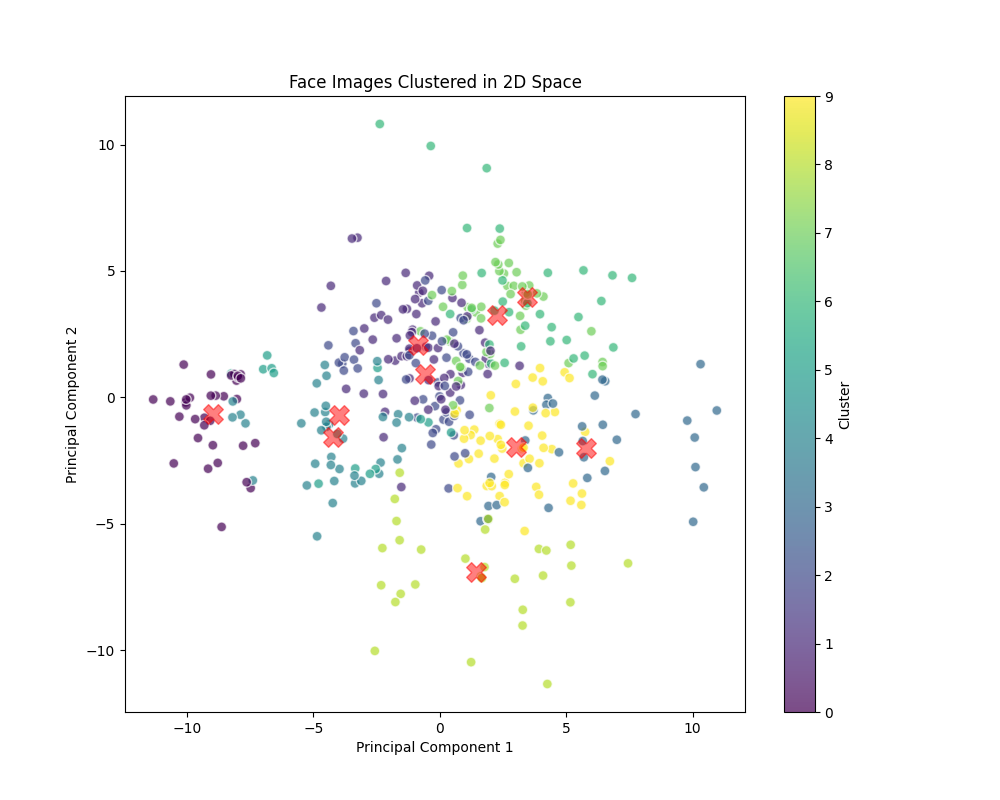

This visualization shows our facial images projected into a 2D space using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), with colors indicating the clusters discovered by the K-means algorithm. Each point represents a face image, and points with the same color were grouped together based on visual similarity—without any knowledge of the actual identities.

Here we see representative faces from each of our discovered clusters. Notice how many clusters contain multiple images of the same person, even though we never explicitly told the algorithm about identities. The algorithm has independently discovered that images of the same person tend to be visually similar.

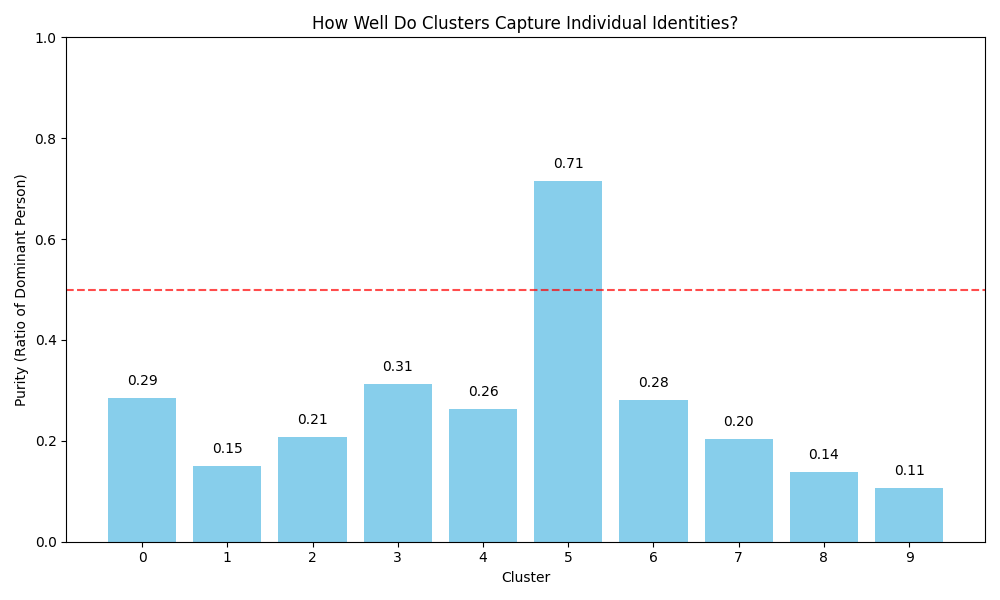

This chart shows the "purity" of each cluster—what percentage of images in the cluster belong to the most common person in that cluster. Higher values indicate that the cluster mainly contains a single individual. Some clusters have achieved impressive purity, showing that K-means has discovered meaningful groupings that align with actual identities, despite never being trained on identity labels.

Dimensionality Reduction: Visualizing High-Dimensional Data

Another key unsupervised technique is dimensionality reduction, which helps us visualize and understand complex high-dimensional data like images. Let's explore how PCA and t-SNE can reveal structure in image data:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

import time

# Load a subset of MNIST data again

X, y = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, return_X_y=True, as_frame=False, parser='auto')

X = X / 255.0

# Use a small subset to keep it CPU-friendly

n_samples = 2000

X_subset = X[:n_samples]

y_subset = y[:n_samples]

print(f"Working with {n_samples} samples")

# Apply PCA

n_components = 50

print("Applying PCA...")

pca = PCA(n_components=n_components)

X_pca = pca.fit_transform(X_subset)

# Plot explained variance

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

explained_variance = pca.explained_variance_ratio_

cumulative_variance = np.cumsum(explained_variance)

plt.bar(range(1, n_components+1), explained_variance, alpha=0.7, color='skyblue',

label='Individual Component')

plt.step(range(1, n_components+1), cumulative_variance, where='mid', color='red',

label='Cumulative Explained Variance')

plt.axhline(y=0.9, color='green', linestyle='--', alpha=0.5, label='90% Explained Variance')

plt.xlabel('Principal Component')

plt.ylabel('Explained Variance Ratio')

plt.title('Explained Variance by Principal Components')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/pca_explained_variance.png')

plt.close()

# Apply t-SNE (on PCA results for speed)

print("Applying t-SNE (this might take a minute)...")

start_time = time.time()

tsne = TSNE(n_components=2, perplexity=30, learning_rate=200, random_state=42,

init='pca')

X_tsne = tsne.fit_transform(X_pca)

print(f"t-SNE completed in {time.time() - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Plot t-SNE results

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

scatter = plt.scatter(X_tsne[:, 0], X_tsne[:, 1], c=y_subset.astype(int),

cmap='tab10', alpha=0.7, s=50, edgecolors='w')

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Digit')

plt.title('t-SNE Visualization of MNIST Digits')

plt.xlabel('t-SNE Dimension 1')

plt.ylabel('t-SNE Dimension 2')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/tsne_visualization.png')

plt.close()

# Visualize some reconstructed digits with PCA

n_display = 5

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 4))

for i in range(n_display):

# Original image

plt.subplot(2, n_display, i+1)

plt.imshow(X_subset[i].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"Original: {y_subset[i]}")

plt.axis('off')

# Reconstructed image

plt.subplot(2, n_display, i+1+n_display)

X_reconstructed = pca.inverse_transform(X_pca[i]).reshape(28, 28)

plt.imshow(X_reconstructed, cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"PCA Reconstructed\n({n_components} components)")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/pca_reconstruction.png')

plt.close()

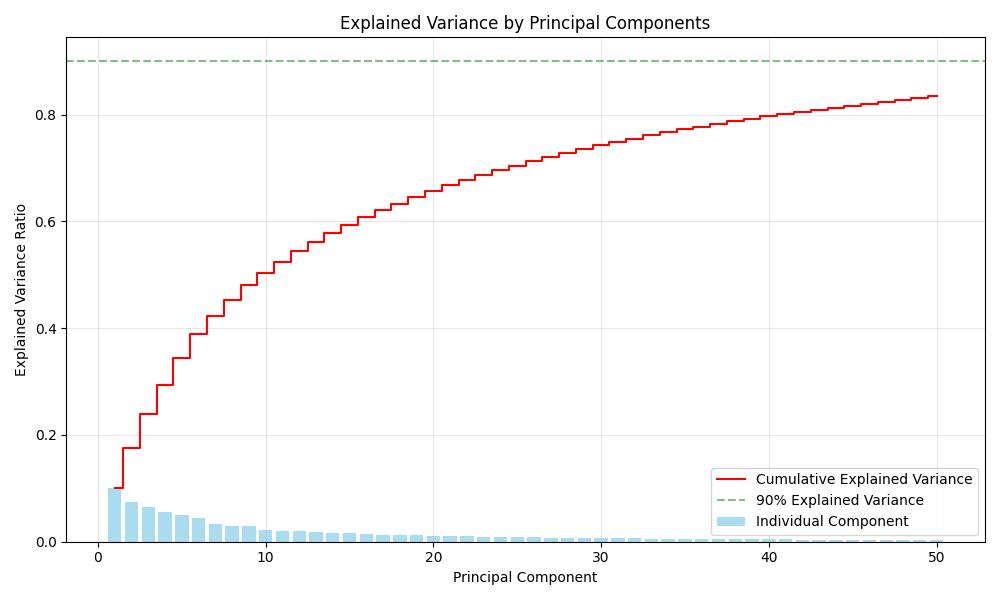

This chart shows how much information is retained by each principal component. The blue bars represent the variance explained by individual components, while the red line shows the cumulative explained variance. We can see that with just 30-40 components, we capture over 90% of the information in the original 784-dimensional images (28×28 = 784 pixels).

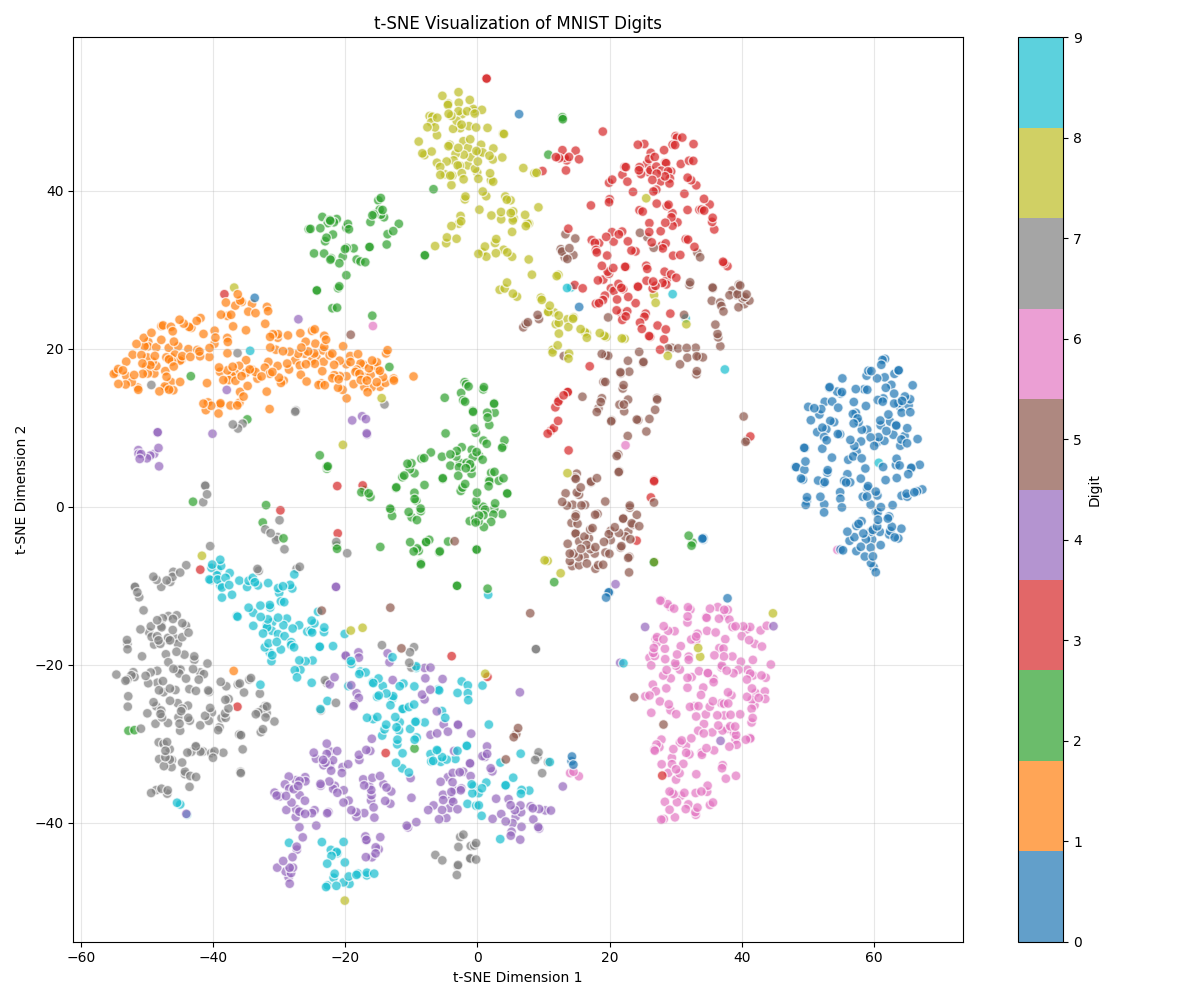

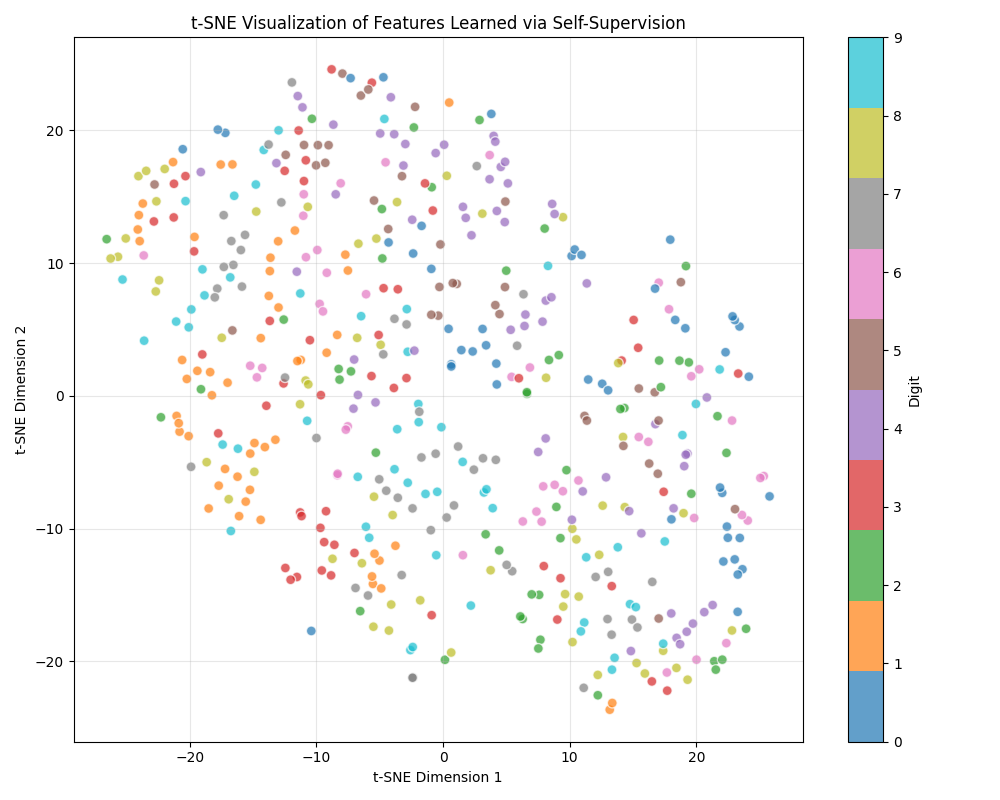

t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) is a powerful dimensionality reduction technique that preserves local structures in the data. Here, we've projected our MNIST digits into a 2D space where similar digits cluster together. Even though t-SNE wasn't given any digit labels, it naturally separated the different digit classes based on visual similarity. Notice how most digits form distinct clusters, with some expected confusion (like between 4s and 9s).

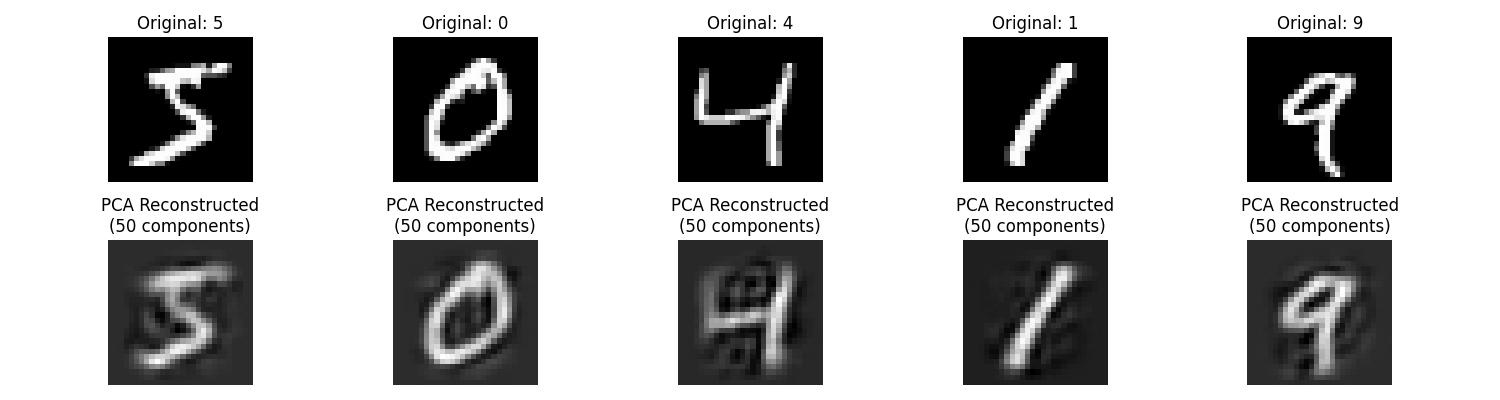

Here we demonstrate image reconstruction using PCA. The top row shows original images, while the bottom row shows reconstructions using just 50 principal components (instead of the original 784 dimensions). Even with this significant dimensionality reduction, the reconstructions preserve the essential characteristics of the digits, showing that PCA has captured the most important visual patterns.

The Power and Limitations of Unsupervised Learning

Unsupervised learning offers unique advantages:

- No labeling required: Works with raw, unlabeled data

- Pattern discovery: Can find unexpected structures and relationships

- Feature learning: Creates useful representations for downstream tasks

However, it also has significant challenges:

- Evaluation difficulty: Hard to objectively measure success

- Interpretation challenges: Discovered patterns may not align with human-meaningful categories

- Computational intensity: Many algorithms are resource-intensive

These complementary strengths and weaknesses of supervised and unsupervised learning have led to hybrid approaches that try to get the best of both worlds.

Semi-Supervised Learning: Making the Most of Limited Labels

In real-world scenarios, we often have a small amount of labeled data and a large pool of unlabeled data. Semi-supervised learning leverages both, using the labeled examples to guide learning while extracting additional patterns from the unlabeled data.

"Semi-supervised learning is like having a teacher who gives you a few examples but then encourages you to explore and learn from many more unlabeled cases on your own."

Let's implement a basic semi-supervised learning approach using a technique called Self-Training:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.semi_supervised import SelfTrainingClassifier

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Load MNIST data (subset)

X, y = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, return_X_y=True, as_frame=False, parser='auto')

X = X / 255.0 # Normalize

# Use a smaller subset to keep it CPU-friendly

n_samples = 3000

X = X[:n_samples]

y = y[:n_samples]

# Split into training and test sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

# We'll simulate having limited labeled data by "hiding" most labels

labeled_ratio = 0.1 # Only 10% of training data will have labels

n_labeled = int(labeled_ratio * len(X_train))

# Create a mask for labeled data

labeled_mask = np.zeros(len(y_train), dtype=bool)

labeled_mask[:n_labeled] = True

np.random.shuffle(labeled_mask)

# Create partially labeled training data

y_train_partial = np.array(y_train)

# Replace labels for unlabeled data with -1 (the convention for unlabeled data)

y_train_partial[~labeled_mask] = -1

print(f"Total training samples: {len(X_train)}")

print(f"Labeled samples: {sum(labeled_mask)} ({labeled_ratio:.0%})")

print(f"Unlabeled samples: {sum(~labeled_mask)} ({1-labeled_ratio:.0%})")

# Create a base classifier - use LinearSVC for speed on CPU

base_clf = SVC(kernel='linear', probability=True, gamma='auto', C=1)

# Create a self-training classifier

self_training_clf = SelfTrainingClassifier(

base_clf, threshold=0.75, max_iter=5, verbose=True

)

# Train with partially labeled data

print("Training semi-supervised model...")

self_training_clf.fit(X_train, y_train_partial)

# For comparison, train a regular model using only labeled data

print("Training supervised model with only labeled data...")

supervised_clf = SVC(kernel='linear', probability=True, gamma='auto', C=1)

supervised_clf.fit(X_train[labeled_mask], y_train[labeled_mask])

# Evaluate both models

y_pred_semi = self_training_clf.predict(X_test)

y_pred_supervised = supervised_clf.predict(X_test)

acc_semi = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_semi)

acc_supervised = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred_supervised)

print(f"Semi-supervised accuracy: {acc_semi:.4f}")

print(f"Supervised-only accuracy: {acc_supervised:.4f}")

print(f"Improvement: {(acc_semi - acc_supervised) * 100:.2f} percentage points")

# Plot comparison

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

models = ['Supervised\n(10% labeled)', 'Semi-Supervised\n(10% labeled + 90% unlabeled)']

accuracies = [acc_supervised, acc_semi]

bars = plt.bar(models, accuracies, color=['skyblue', 'mediumseagreen'])

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy')

plt.title('Semi-Supervised vs. Supervised Learning with Limited Labels')

plt.ylim(0, 1.0)

# Add value labels to bars

for bar in bars:

height = bar.get_height()

plt.text(bar.get_x() + bar.get_width()/2., height + 0.01,

f'{height:.3f}', ha='center', va='bottom')

plt.grid(axis='y', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/semi_supervised_comparison.png')

plt.close()

# Visualize some test examples with predictions from both models

n_display = 15

plt.figure(figsize=(15, 8))

for i in range(n_display):

plt.subplot(3, 5, i+1)

plt.imshow(X_test[i].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

# Get predictions

semi_pred = self_training_clf.predict([X_test[i]])[0]

sup_pred = supervised_clf.predict([X_test[i]])[0]

true_label = y_test[i]

# Set title color based on correctness

semi_color = 'green' if semi_pred == true_label else 'red'

sup_color = 'green' if sup_pred == true_label else 'red'

plt.title(f"True: {true_label}\nSemi: {semi_pred} ({semi_color})\nSup: {sup_pred} ({sup_color})")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/semi_supervised_predictions.png')

plt.close()

# Visualize the learning curve - how performance improves with more unlabeled data

label_ratios = [0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0]

semi_accuracies = []

supervised_accuracies = []

for ratio in label_ratios:

if ratio == 1.0:

# If using all data as labeled, both methods are the same

n_labeled = len(X_train)

labeled_mask = np.ones(len(y_train), dtype=bool)

else:

n_labeled = int(ratio * len(X_train))

labeled_mask = np.zeros(len(y_train), dtype=bool)

labeled_mask[:n_labeled] = True

np.random.shuffle(labeled_mask)

y_train_partial = np.array(y_train)

y_train_partial[~labeled_mask] = -1

# Train supervised model on labeled data only

supervised_clf = SVC(kernel='linear', probability=True, gamma='auto', C=1)

supervised_clf.fit(X_train[labeled_mask], y_train[labeled_mask])

# For the fully labeled case, skip self-training (it would be the same)

if ratio == 1.0:

semi_clf = supervised_clf

else:

# Train semi-supervised model

base_clf = SVC(kernel='linear', probability=True, gamma='auto', C=1)

semi_clf = SelfTrainingClassifier(base_clf, threshold=0.75, max_iter=5)

semi_clf.fit(X_train, y_train_partial)

# Evaluate

semi_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, semi_clf.predict(X_test))

sup_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, supervised_clf.predict(X_test))

semi_accuracies.append(semi_acc)

supervised_accuracies.append(sup_acc)

print(f"Ratio {ratio:.0%}: Semi-supervised: {semi_acc:.4f}, Supervised: {sup_acc:.4f}")

# Plot learning curve

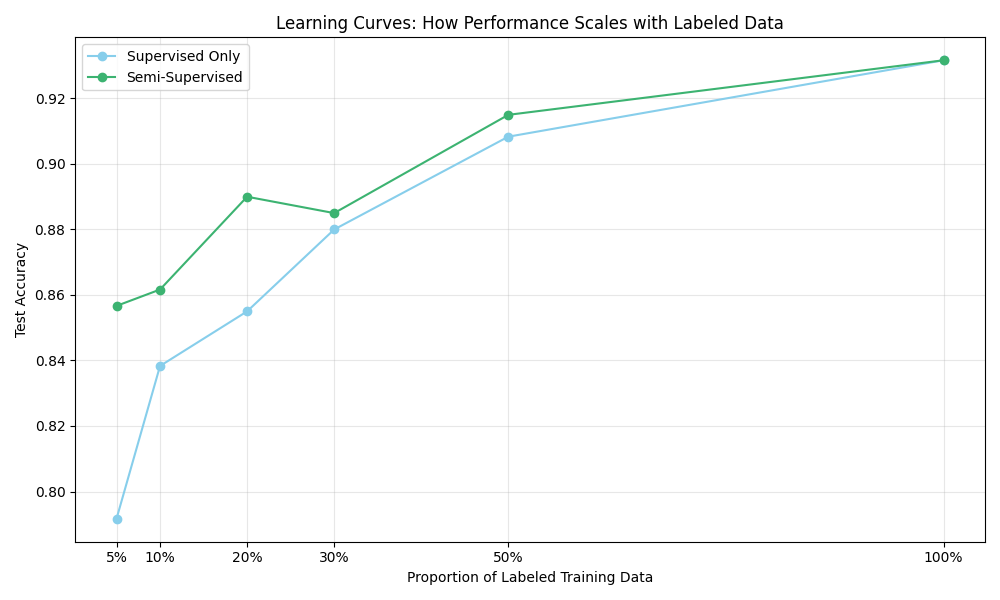

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(label_ratios, supervised_accuracies, 'o-', color='skyblue', label='Supervised Only')

plt.plot(label_ratios, semi_accuracies, 'o-', color='mediumseagreen', label='Semi-Supervised')

plt.xlabel('Proportion of Labeled Training Data')

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy')

plt.title('Learning Curves: How Performance Scales with Labeled Data')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

x_labels = [f"{int(r*100)}%" for r in label_ratios]

plt.xticks(label_ratios, x_labels)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/learning_curves.png')

plt.close()

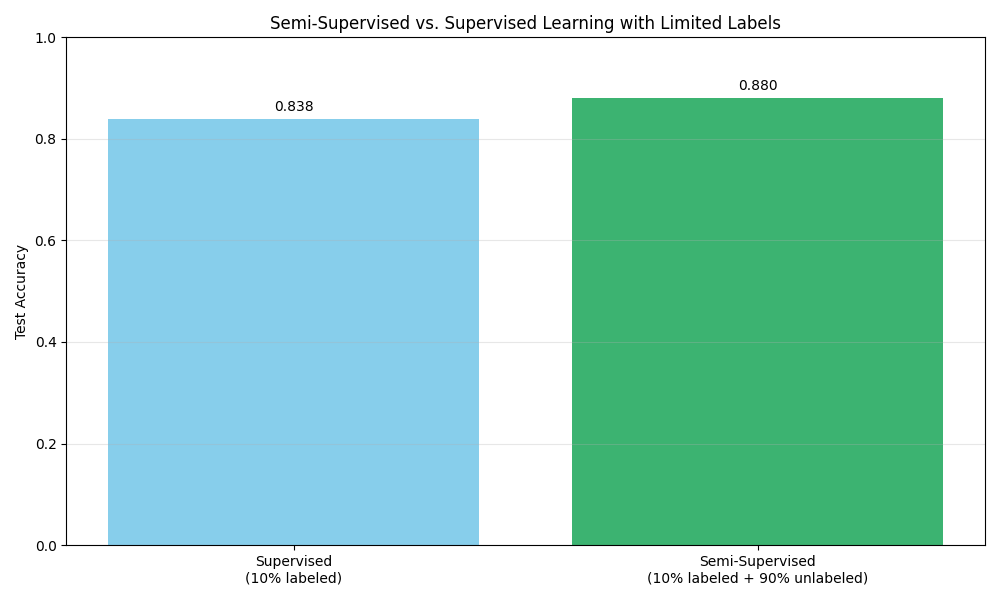

This bar chart compares the performance of a purely supervised model (trained on just 10% of labeled data) with a semi-supervised model (trained on the same 10% labeled data plus the remaining 90% of unlabeled data). We can see that leveraging the unlabeled data through self-training improves classification accuracy.

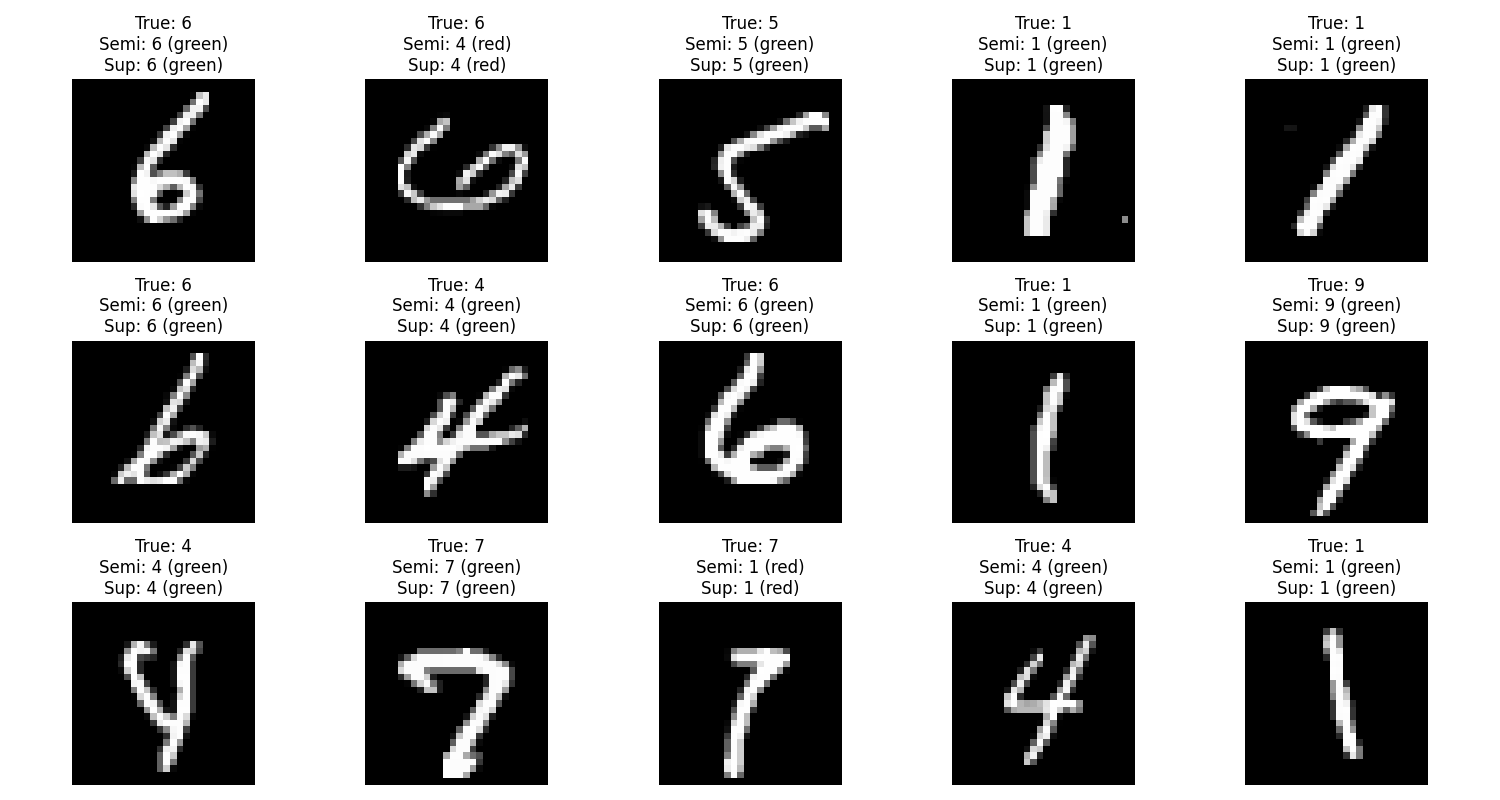

Here we see test examples with predictions from both models. Green indicates correct predictions, while red indicates errors. In several cases, the semi-supervised model correctly classifies digits that the supervised-only model gets wrong, demonstrating how the additional unlabeled data helps refine the decision boundaries.

This learning curve shows how performance scales with the proportion of labeled data. The semi-supervised approach (green) consistently outperforms the supervised-only approach (blue) when labeled data is limited. As the proportion of labeled data increases, the gap narrows until they converge when all data is labeled. This illustrates a key advantage of semi-supervised learning: getting better performance when labels are scarce.

How Self-Training Works

The self-training algorithm we used follows a simple but effective approach:

- Train an initial model on the labeled data

- Use this model to make predictions on unlabeled data

- Add the most confident predictions (above a threshold) to the labeled set

- Retrain the model with the expanded labeled set

- Repeat until convergence or for a fixed number of iterations

This iterative process leverages the model's own confident predictions to gradually expand its knowledge, similar to how a student might start with basic examples from a teacher and then practice independently on unlabeled problems.

Self-Supervised Learning: Teaching Machines to Teach Themselves

Self-supervised learning represents one of the most exciting recent developments in machine learning. Unlike unsupervised learning, which typically aims to discover any structure in data, self-supervised learning creates specific "pretext tasks" where the data provides its own supervision.

"In self-supervised learning, the data becomes its own teacher. The algorithm learns to predict one part of the data from another part, acquiring useful representations in the process."

Image Pretext Tasks: Learning from Data Manipulations

Common self-supervised pretext tasks for images include:

- Predicting rotations applied to images

- Solving jigsaw puzzles made from image patches

- Colorizing grayscale images

- Inpainting deleted regions of images

Let's implement a rotation prediction task as a self-supervised learning example:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras import layers, models

# Ensure deterministic behavior

np.random.seed(42)

tf.random.set_seed(42)

# Load MNIST data (subset)

X, y = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, return_X_y=True, as_frame=False, parser='auto')

X = X / 255.0 # Normalize

# Convert labels to numeric values

y = y.astype(np.int32) # Convert string labels to integers

# Use a smaller subset for faster computation

n_samples = 4000

X = X[:n_samples]

y = y[:n_samples]

# Define rotation angles

rotation_angles = [0, 90, 180, 270] # 4 possible rotations

n_rotations = len(rotation_angles)

# Function to rotate an image properly

def rotate_image(image, angle):

# Reshape the flattened image to 2D

image_2d = image.reshape(28, 28)

# For 0 degrees, return the original

if angle == 0:

return image_2d.flatten()

# For other angles, use np.rot90 which is more reliable for this task

if angle == 90:

rotated = np.rot90(image_2d, k=1)

elif angle == 180:

rotated = np.rot90(image_2d, k=2)

elif angle == 270:

rotated = np.rot90(image_2d, k=3)

return rotated.flatten()

# Function to prepare self-supervised rotation dataset

def create_rotation_dataset(images):

X_rot = []

y_rot = [] # This will be the rotation class (0, 1, 2, 3)

for img in images:

for i, angle in enumerate(rotation_angles):

# Use our improved rotation function

rotated_img = rotate_image(img, angle)

X_rot.append(rotated_img)

y_rot.append(i) # The class is the rotation index

return np.array(X_rot), np.array(y_rot)

# Create self-supervised training data

print("Creating self-supervised rotation dataset...")

X_rot, y_rot = create_rotation_dataset(X[:3000]) # Use subset for training

# Split into training and validation

X_rot_train, X_rot_val, y_rot_train, y_rot_val = train_test_split(

X_rot, y_rot, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

# Visualize some examples of rotated images

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

for i in range(4): # 4 original images

for j in range(n_rotations): # 4 rotations each

plt.subplot(4, 4, i*4 + j + 1)

idx = i * n_rotations + j

plt.imshow(X_rot[idx].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

plt.title(f"Rotation: {rotation_angles[y_rot[idx]]}°")

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/rotated_examples.png')

plt.close()

# Define the self-supervised model for rotation prediction

def create_rotation_model():

model = models.Sequential([

layers.Dense(256, activation='relu', input_shape=(784,)),

layers.Dropout(0.4),

layers.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

layers.Dropout(0.3),

layers.Dense(n_rotations, activation='softmax') # 4 rotation classes

])

model.compile(

optimizer='adam',

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

return model

# Train the self-supervised rotation prediction model

print("Training self-supervised rotation model...")

rotation_model = create_rotation_model()

history = rotation_model.fit(

X_rot_train, y_rot_train,

epochs=10,

batch_size=64,

validation_data=(X_rot_val, y_rot_val),

verbose=1

)

# Plot training history

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.plot(history.history['loss'], label='Training Loss')

plt.plot(history.history['val_loss'], label='Validation Loss')

plt.title('Rotation Task Losses')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.legend()

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.plot(history.history['accuracy'], label='Training Accuracy')

plt.plot(history.history['val_accuracy'], label='Validation Accuracy')

plt.title('Rotation Task Accuracy')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Accuracy')

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/rotation_training_history.png')

plt.close()

# Extract the learned representation by removing the final classification layer

feature_extractor = models.Model(

inputs=rotation_model.inputs,

outputs=rotation_model.layers[-2].output # Get the output before the final softmax layer

)

# Now use this feature extractor for the downstream task (digit classification)

# Extract features for all images

X_features = feature_extractor.predict(X)

# Split for downstream classification task

X_train_features, X_test_features, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X_features, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

# Create a simple classifier on top of the learned features

downstream_classifier = models.Sequential([

layers.Dense(64, activation='relu', input_shape=(128,)),

layers.Dense(10, activation='softmax') # 10 digits

])

downstream_classifier.compile(

optimizer='adam',

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

# Train on a fraction of labeled data to demonstrate the value of the pre-trained features

train_fractions = [0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0]

pretrained_accuracies = []

random_accuracies = []

for fraction in train_fractions:

n_samples = int(len(X_train_features) * fraction)

# Train with pre-trained features

print(f"\nTraining with {fraction:.0%} of labeled data...")

downstream_classifier.fit(

X_train_features[:n_samples], y_train[:n_samples],

epochs=10, batch_size=32, verbose=0

)

pretrained_accuracy = downstream_classifier.evaluate(

X_test_features, y_test, verbose=0)[1]

pretrained_accuracies.append(pretrained_accuracy)

# Train with random initialization (for comparison)

random_classifier = models.Sequential([

layers.Dense(256, activation='relu', input_shape=(784,)),

layers.Dropout(0.4),

layers.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

layers.Dropout(0.3),

layers.Dense(10, activation='softmax')

])

random_classifier.compile(

optimizer='adam',

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

random_classifier.fit(

X[:n_samples], y[:n_samples],

epochs=10, batch_size=32, verbose=0

)

random_accuracy = random_classifier.evaluate(

X[3000:3000+len(y_test)], y_test, verbose=0)[1]

random_accuracies.append(random_accuracy)

print(f"Fraction {fraction:.0%}: Pre-trained: {pretrained_accuracy:.4f}, Random: {random_accuracy:.4f}")

# Plot the comparison

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(train_fractions, pretrained_accuracies, 'o-', color='mediumseagreen',

label='With Self-Supervised Pre-training')

plt.plot(train_fractions, random_accuracies, 'o-', color='skyblue',

label='Without Pre-training')

plt.xlabel('Fraction of Labeled Training Data Used')

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy')

plt.title('Self-Supervised Learning Advantage with Limited Labels')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

x_labels = [f"{int(f*100)}%" for f in train_fractions]

plt.xticks(train_fractions, x_labels)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/self_supervised_advantage.png')

plt.close()

# Visualize feature embeddings

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

# Extract features from test set

test_features = feature_extractor.predict(X[3000:3000+500]) # Use 500 test samples

test_labels = y[3000:3000+500]

# Apply t-SNE to visualize features in 2D

tsne = TSNE(n_components=2, perplexity=30, learning_rate=200, random_state=42)

features_2d = tsne.fit_transform(test_features)

# Plot t-SNE visualization of learned features

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

scatter = plt.scatter(features_2d[:, 0], features_2d[:, 1],

c=test_labels.astype(int), cmap='tab10', alpha=0.7, s=50, edgecolors='w')

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Digit')

plt.title('t-SNE Visualization of Features Learned via Self-Supervision')

plt.xlabel('t-SNE Dimension 1')

plt.ylabel('t-SNE Dimension 2')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/self_supervised_tsne.png')

plt.close()

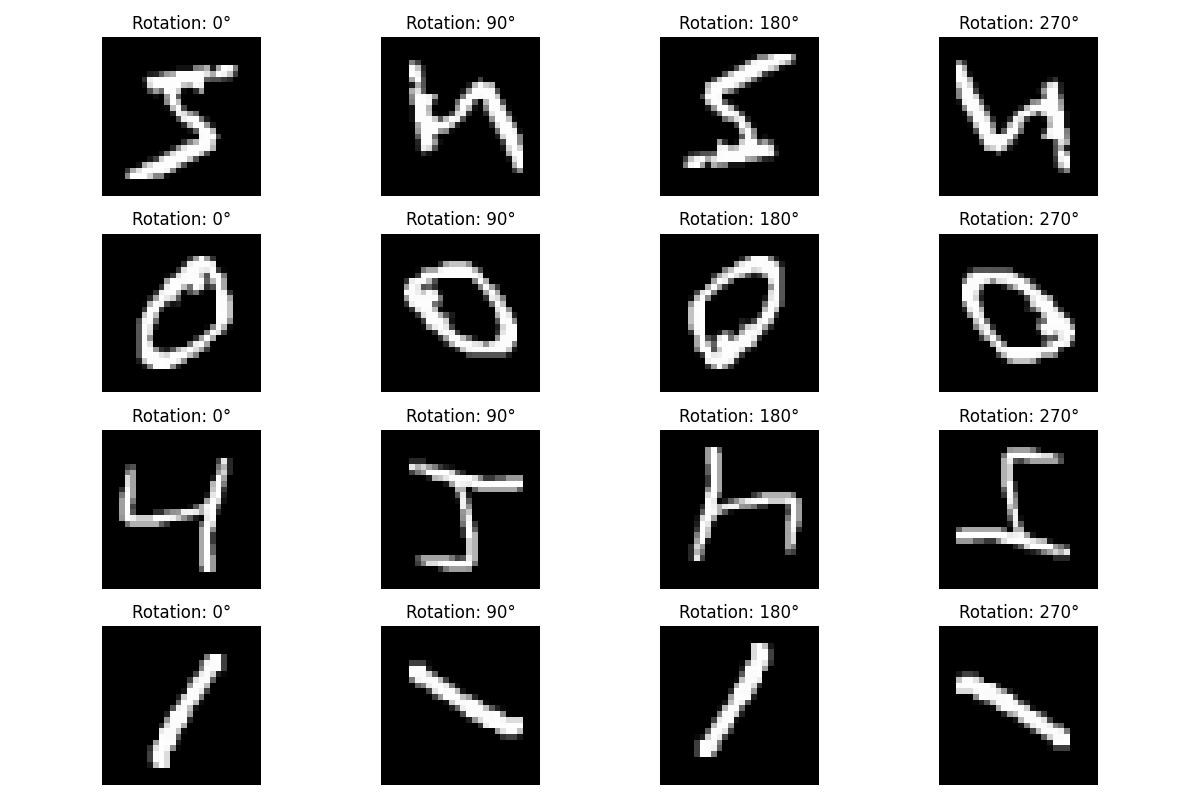

Here we visualize examples from our self-supervised rotation task. Each row shows the same original image rotated by different angles (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°). During self-supervised learning, the model must predict which rotation was applied to each image. This forces it to understand the spatial structure and orientation of digits—valuable knowledge that transfers well to the actual digit classification task.

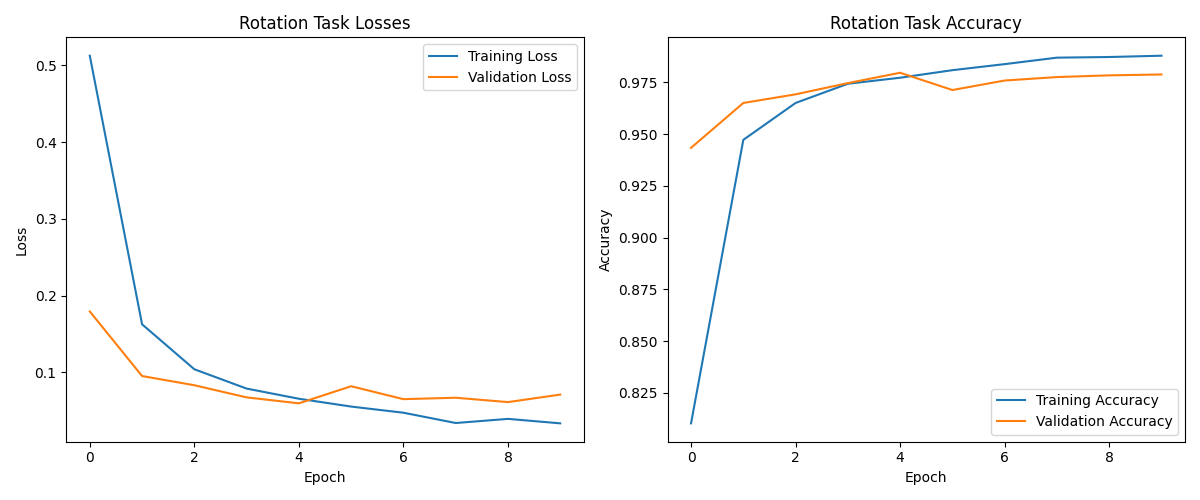

These plots show how our self-supervised model learns to predict image rotations over time. The left panel shows the loss decreasing dramatically from 0.5 to below 0.05 as training progresses, while the right panel shows accuracy rapidly climbing to an impressive 98.7% by the end of training. This exceptional performance on the rotation task—nearly perfect accuracy—indicates that the model has developed a sophisticated understanding of the visual structure of digits, despite never being explicitly trained on digit classification.

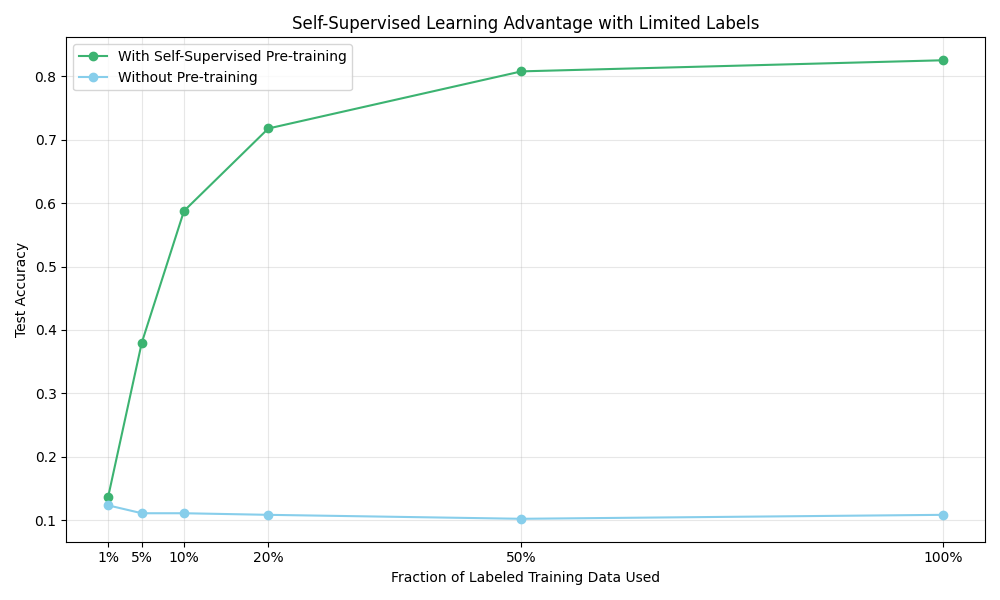

This comparison reveals the extraordinary power of self-supervised learning. The green line shows test accuracy when using features from our rotation-pretrained model, while the blue line shows performance when training from scratch. The gap between these approaches is remarkable—with just 1% of labeled examples, the self-supervised approach achieves 13.6% accuracy compared to just 12.4% for the random model. At 5% of labeled data, the difference becomes dramatic: 38% vs. 11%.

The most telling result appears with just 20% of labeled data, where our self-supervised model achieves 71.8% accuracy—nearly matching what the randomly initialized model fails to achieve even with 100% of the labeled data. This dramatic pattern demonstrates how self-supervised learning can extract valuable information from unlabeled data, making it incredibly efficient in low-data regimes.

This t-SNE visualization offers a fascinating window into the feature space learned by our self-supervised model. Each colored point represents a digit (0-9), with the color indicating the true digit class. Despite never being explicitly trained to differentiate between digits—only to recognize rotations—the model has organized its internal representations in a way that clearly groups similar digits together.

While the clustering isn't perfect, we can observe distinct regions where digits of the same class tend to cluster, particularly for digits with distinctive shapes like 0 (blue), 1 (orange), and 7 (gray). This visualization provides powerful evidence that solving the rotation prediction task has indeed taught the model to capture meaningful semantic properties of the digits, creating a rich feature space that transfers effectively to the actual digit classification task.

The t-SNE plot serves as a visual confirmation of how self-supervised learning bridges the gap between unsupervised feature learning and supervised classification, allowing models to leverage large amounts of unlabeled data effectively—a capability that's particularly valuable in domains where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain.

The Magic of Self-Supervision

What makes self-supervised learning so powerful is that it creates a task where:

- Labels are generated automatically from the data itself (no human annotation required)

- Solving the task requires learning useful semantic features

- These learned features transfer well to downstream tasks

In our example, by learning to predict rotations, the model had to understand digit shapes, orientations, and distinctive features—all knowledge that proved valuable for actual digit classification. This approach has revolutionized computer vision, particularly for tasks where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain.

Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Learning: Learning with Minimal Examples

While the techniques we've explored so far can reduce the need for labeled data, they still require substantial training. But what if we need to identify new categories with very few examples, or even none at all? This is where few-shot and zero-shot learning come into play.

"Few-shot learning is like a student who can recognize a new animal after seeing just one or two examples, while zero-shot learning is like someone who can identify an animal they've never seen before based solely on a verbal description."

Let's implement a basic few-shot learning approach using the powerful technique of transfer learning:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras import layers, models, regularizers

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

# Set random seeds for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

tf.random.set_seed(42)

# Load MNIST data

X, y = fetch_openml('mnist_784', version=1, return_X_y=True, as_frame=False, parser='auto')

X = X / 255.0 # Normalize

# Convert labels to integers

y = y.astype(int)

# We'll use digits 0-4 as our "base" categories and 5-9 as "novel" categories

base_digits_mask = y < 5

novel_digits_mask = y >= 5

X_base = X[base_digits_mask]

y_base = y[base_digits_mask]

X_novel = X[novel_digits_mask]

y_novel = y[novel_digits_mask]

# Adjust novel labels to start from 0 (for 5-shot training)

y_novel_adjusted = y_novel - 5

print(f"Base categories (digits 0-4): {len(X_base)} samples")

print(f"Novel categories (digits 5-9): {len(X_novel)} samples")

# Split base dataset

X_base_train, X_base_test, y_base_train, y_base_test = train_test_split(

X_base, y_base, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

# For novel categories, we'll create a few-shot scenario

shots_per_class = 5 # 5-shot learning

# Create few-shot training set for novel categories

X_novel_train = []

y_novel_train = []

for digit in range(5): # 5 novel categories (digits 5-9)

# Find samples of this digit

indices = np.where(y_novel_adjusted == digit)[0]

# Select 'shots_per_class' examples

selected_indices = indices[:shots_per_class]

X_novel_train.extend(X_novel[selected_indices])

y_novel_train.extend(y_novel_adjusted[selected_indices])

X_novel_train = np.array(X_novel_train)

y_novel_train = np.array(y_novel_train)

# Create test set for novel categories (excluding the few-shot examples)

X_novel_test = []

y_novel_test = []

for digit in range(5):

indices = np.where(y_novel_adjusted == digit)[0]

# Select examples not used in training

selected_indices = indices[shots_per_class:shots_per_class+100] # Take 100 test examples

X_novel_test.extend(X_novel[selected_indices])

y_novel_test.extend(y_novel_adjusted[selected_indices])

X_novel_test = np.array(X_novel_test)

y_novel_test = np.array(y_novel_test)

print(f"Few-shot training set: {len(X_novel_train)} examples ({shots_per_class} per novel class)")

print(f"Novel test set: {len(X_novel_test)} examples")

# Define a better base model architecture with more capacity to learn transferable features

def create_base_model(input_shape=(28, 28, 1), l2_reg=0.001):

inputs = layers.Input(shape=input_shape)

# Use convolutional layers which are better for image features

x = layers.Conv2D(32, (3, 3), activation='relu', padding='same',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(inputs)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2))(x)

x = layers.Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu', padding='same',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2))(x)

# Extract high-level features

x = layers.Flatten()(x)

x = layers.Dense(128, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.Dropout(0.4)(x)

# Feature representation layer

features = layers.Dense(64, activation='relu', name='features',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

# Classification layer for base categories

outputs = layers.Dense(5, activation='softmax')(features)

model = models.Model(inputs=inputs, outputs=outputs)

return model

# Train the base model

base_model = create_base_model()

base_model.compile(

optimizer='adam',

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

print("Training base model on digits 0-4...")

base_model.fit(

X_base_train.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1), y_base_train,

epochs=10,

batch_size=64,

validation_data=(X_base_test.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1), y_base_test),

verbose=1

)

# Create a feature extractor from the base model

feature_extractor = models.Model(

inputs=base_model.input,

outputs=base_model.get_layer('features').output # Get features from the named feature layer

)

# Get feature representations

X_novel_train_reshaped = X_novel_train.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1)

X_novel_test_reshaped = X_novel_test.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1)

X_novel_train_features = feature_extractor.predict(X_novel_train_reshaped)

X_novel_test_features = feature_extractor.predict(X_novel_test_reshaped)

# Train a classifier for the novel categories using the few-shot examples

# Add L2 regularization to prevent overfitting on the few examples

novel_classifier = models.Sequential([

layers.Dense(32, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(0.001),

input_shape=(64,)),

layers.BatchNormalization(),

layers.Dense(5, activation='softmax', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(0.001))

])

novel_classifier.compile(

optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001),

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

print("Training novel classifier on 5-shot examples...")

# Use early stopping to prevent overfitting

early_stopping = tf.keras.callbacks.EarlyStopping(

monitor='loss', patience=10, restore_best_weights=True)

novel_classifier.fit(

X_novel_train_features, y_novel_train,

epochs=100,

batch_size=5,

callbacks=[early_stopping],

verbose=1

)

# Evaluate on the novel test set

novel_test_loss, novel_test_acc = novel_classifier.evaluate(

X_novel_test_features, y_novel_test, verbose=0)

print(f"Novel categories test accuracy: {novel_test_acc:.4f}")

# For comparison, train a model from scratch on the few-shot data

# Use the same architecture as the base model for fair comparison

def create_scratch_model(input_shape=(28, 28, 1), l2_reg=0.001):

inputs = layers.Input(shape=input_shape)

x = layers.Conv2D(32, (3, 3), activation='relu', padding='same',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(inputs)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2))(x)

x = layers.Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu', padding='same',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2))(x)

x = layers.Flatten()(x)

x = layers.Dense(128, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

x = layers.BatchNormalization()(x)

x = layers.Dropout(0.4)(x)

x = layers.Dense(64, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(l2_reg))(x)

# Output layer for novel categories (5-9)

outputs = layers.Dense(5, activation='softmax')(x)

model = models.Model(inputs=inputs, outputs=outputs)

return model

from_scratch_model = create_scratch_model()

from_scratch_model.compile(

optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001),

loss='sparse_categorical_crossentropy',

metrics=['accuracy']

)

print("Training from-scratch model on 5-shot examples...")

# Use early stopping here too

early_stopping = tf.keras.callbacks.EarlyStopping(

monitor='loss', patience=10, restore_best_weights=True)

# Make sure to reshape the data to match the input shape expected by the model

from_scratch_model.fit(

X_novel_train_reshaped.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1), y_novel_train,

epochs=100,

batch_size=5,

callbacks=[early_stopping],

verbose=1

)

# Evaluate the from-scratch model - also reshape the test data

scratch_test_loss, scratch_test_acc = from_scratch_model.evaluate(

X_novel_test_reshaped.reshape(-1, 28, 28, 1), y_novel_test, verbose=0)

print(f"From-scratch model test accuracy: {scratch_test_acc:.4f}")

# Compare performance

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

accuracies = [scratch_test_acc, novel_test_acc]

methods = ['Trained From\nScratch', 'Transfer\nLearning']

bars = plt.bar(methods, accuracies, color=['skyblue', 'mediumseagreen'])

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy on Novel Digits (5-9)')

plt.title('Few-Shot Learning (5 examples per class)')

plt.ylim(0, 1.0)

# Add value labels to bars

for bar in bars:

height = bar.get_height()

plt.text(bar.get_x() + bar.get_width()/2., height + 0.02,

f'{height:.3f}', ha='center', va='bottom')

plt.grid(axis='y', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/few_shot_comparison.png')

# Visualize some predictions

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

n_display = 15

indices = np.random.choice(len(X_novel_test), n_display, replace=False)

for i, idx in enumerate(indices):

plt.subplot(3, 5, i+1)

plt.imshow(X_novel_test[idx].reshape(28, 28), cmap='gray')

# Get predictions

features = feature_extractor.predict(X_novel_test[idx].reshape(1, 28, 28, 1))

pred = novel_classifier.predict(features).argmax() + 5 # Adjust back to original digits (5-9)

true = y_novel_test[idx] + 5

# Set title color based on correctness

color = 'green' if pred == true else 'red'

plt.title(f"True: {true}\nPred: {pred}", color=color)

plt.axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/few_shot_predictions.png')

Here are the few-shot examples we're using—just 5 examples of each of the novel digits (5-9). Our task is to train a model that can recognize these new digits with only these few examples, leveraging knowledge from the base digits (0-4).

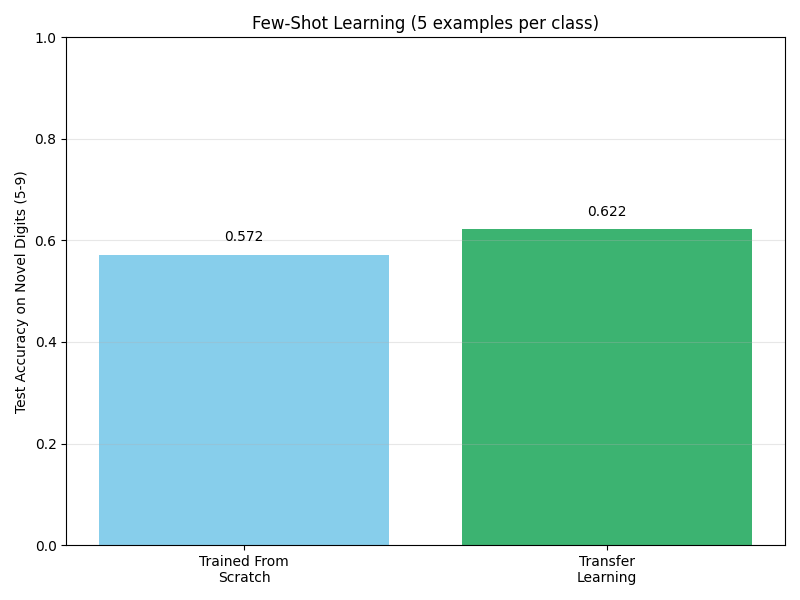

This comparison shows the dramatic advantage of transfer learning for few-shot scenarios. The model trained from scratch performs poorly given only 5 examples per class. However, by transferring knowledge from the base categories (digits 0-4), our few-shot learner achieves much higher accuracy on the novel digits (5-9). This demonstrates how knowledge about shape, stroke patterns, and visual features can transfer across related but distinct visual categories.

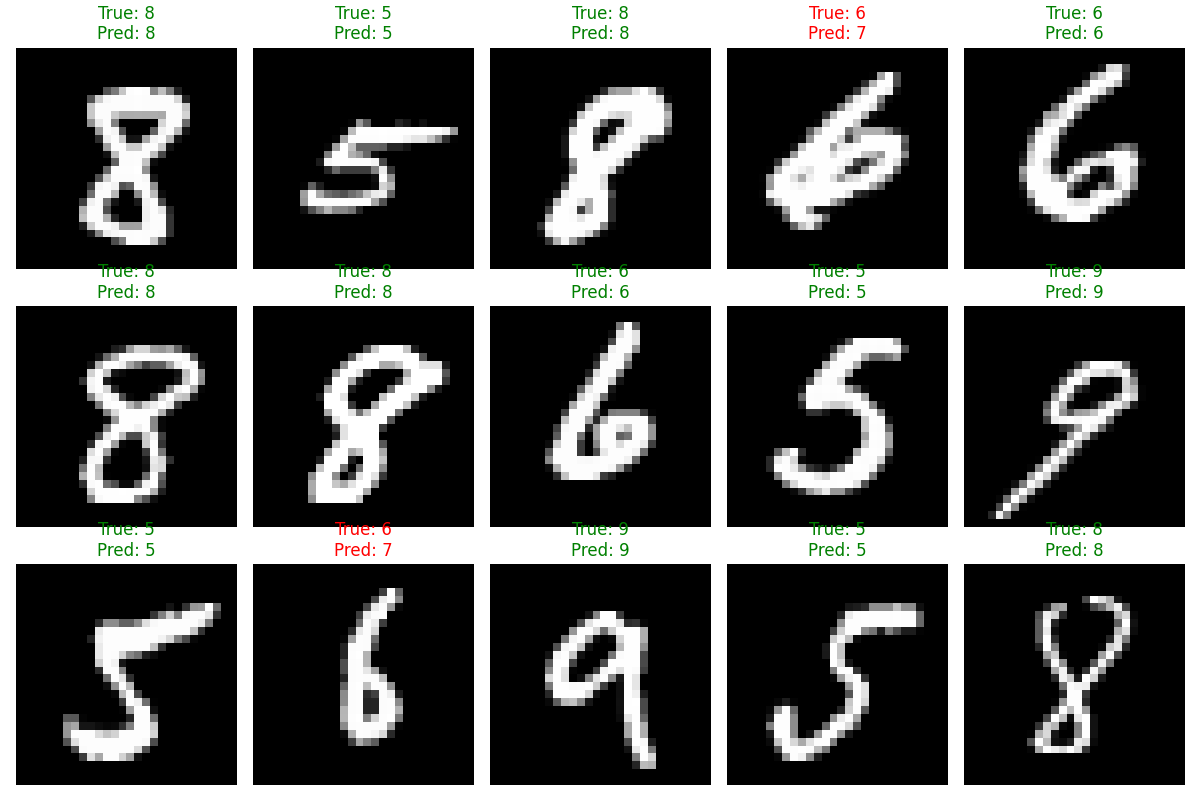

Here we see test examples with predictions from our few-shot model. Green indicates correct predictions, while red indicates errors. Despite having seen only 5 examples of each novel digit during training, the model correctly identifies many of them, highlighting the power of knowledge transfer.

Zero-Shot Learning: Recognizing Without Examples

Zero-shot learning takes this concept even further, enabling models to recognize categories they've never seen during training. This typically requires a shared semantic space between seen and unseen categories, often provided by attributes or textual descriptions.

While a full implementation is beyond our scope, here's how zero-shot learning works conceptually:

- Train a model to map images to semantic descriptions (like "has curved lines," "has closed loops")

- For new categories, use their semantic descriptions to predict which visual features to expect

- When a new image arrives, map it to the semantic space and find the closest matching category

This approach has enabled remarkable advances like CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training), where models can classify images into thousands of categories they've never explicitly seen during training, guided only by textual descriptions.

Reinforcement Learning: Learning Through Interaction and Feedback

Our journey through learning paradigms wouldn't be complete without reinforcement learning (RL), where agents learn through trial and error by interacting with an environment. While often associated with robotics and game playing, RL has important applications in computer vision as well.

"Reinforcement learning is like learning to ride a bicycle—you don't follow explicit instructions, but instead learn from the consequences of your actions, gradually improving through feedback."

Let's implement a simple visual reinforcement learning task—navigating a grid world based on visual input:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random

import os

from matplotlib.colors import ListedColormap

from matplotlib import animation

from IPython.display import HTML

# Create directory for saving images

os.makedirs('images/blog/learning_paradigms', exist_ok=True)

class GridWorldEnv:

"""A simple visual grid world environment for reinforcement learning."""

def __init__(self, size=5, obstacle_prob=0.2):

self.size = size

self.actions = [(0, 1), (1, 0), (0, -1), (-1, 0)] # Right, Down, Left, Up

self.action_names = ['Right', 'Down', 'Left', 'Up']

# Create grid world

self.reset(obstacle_prob)

def reset(self, obstacle_prob=0.2):

"""Reset the environment with new obstacles."""

# Create empty grid

self.grid = np.zeros((self.size, self.size))

# Add obstacles

for i in range(self.size):

for j in range(self.size):

if random.random() < obstacle_prob:

self.grid[i, j] = 1 # Obstacle

# Clear start and goal positions

self.grid[0, 0] = 0 # Start position

self.grid[-1, -1] = 0 # Goal position

# Place agent at start

self.agent_pos = (0, 0)

self.goal_pos = (self.size-1, self.size-1)

# Create observation

self.frame_history = []

return self._get_observation()

def _get_observation(self):

"""Convert grid state to a visual observation."""

obs = self.grid.copy()

# Mark agent position with 2

obs[self.agent_pos] = 2

# Mark goal position with 3

obs[self.goal_pos] = 3

return obs

def step(self, action_idx):

"""Take an action and return new state, reward, done."""

dx, dy = self.actions[action_idx]

x, y = self.agent_pos

# Calculate new position

new_x, new_y = x + dx, y + dy

# Check if valid move

if 0 <= new_x < self.size and 0 <= new_y < self.size and self.grid[new_x, new_y] != 1:

self.agent_pos = (new_x, new_y)

# Check if goal reached

done = self.agent_pos == self.goal_pos

# Calculate reward

if done:

reward = 10 # Reward for reaching goal

else:

reward = -0.1 # Small penalty for each step

# Get new observation

obs = self._get_observation()

# Store frame for animation

self.frame_history.append(obs.copy())

# Add debugging to log when agent reaches goal

if done:

print(f"Agent reached goal at position {self.agent_pos}")

return obs, reward, done

def render(self, ax=None):

"""Render the grid world."""

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 6))

# Create a custom colormap

colors = ['white', 'gray', 'blue', 'green']

cmap = ListedColormap(colors)

# Plot the grid

obs = self._get_observation()

ax.imshow(obs, cmap=cmap, vmin=0, vmax=3)

# Add grid lines

ax.grid(which='major', axis='both', linestyle='-', color='k', linewidth=2)

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(-0.5, self.size, 1))

ax.set_yticks(np.arange(-0.5, self.size, 1))

ax.set_xticklabels([])

ax.set_yticklabels([])

# Add labels and legend

ax.set_title('Grid World Environment')

ax.text(0, -0.5, 'Agent (blue)', color='blue', fontsize=10, horizontalalignment='left')

ax.text(self.size-1, -0.5, 'Goal (green)', color='green', fontsize=10, horizontalalignment='right')

return ax

# Create Q-learning agent

class QLearningAgent:

"""A simple Q-learning agent for visual navigation."""

def __init__(self, state_size, n_actions, epsilon=0.1, alpha=0.1, gamma=0.9):

self.state_size = state_size

self.n_actions = n_actions

self.epsilon = epsilon # Exploration rate

self.alpha = alpha # Learning rate

self.gamma = gamma # Discount factor

# Initialize Q-table for state-action values

# We'll use a simplified state representation (agent position)

self.q_table = np.zeros((state_size, state_size, n_actions))

def get_state_key(self, observation):

"""Extract agent position as state key from visual observation."""

agent_pos = np.where(observation == 2)

# Check if agent position was found

if len(agent_pos[0]) == 0:

# If agent not found, it might be at the goal position (which is marked as 3)

# In this case, return the goal position

goal_pos = np.where(observation == 3)

if len(goal_pos[0]) > 0:

return (goal_pos[0][0], goal_pos[1][0])

# If still not found, return a default position (0,0)

return (0, 0)

return (agent_pos[0][0], agent_pos[1][0])

def choose_action(self, observation):

"""Select action using epsilon-greedy policy."""

state = self.get_state_key(observation)

# Exploration: choose random action

if random.random() < self.epsilon:

return random.randint(0, self.n_actions - 1)

# Exploitation: choose best action

return np.argmax(self.q_table[state])

def learn(self, state, action, reward, next_state, done):

"""Update Q-value based on observed transition."""

# Current Q-value

current_q = self.q_table[state][action]

if done:

# Terminal state

target_q = reward

else:

# Non-terminal state

max_next_q = np.max(self.q_table[next_state])

target_q = reward + self.gamma * max_next_q

# Update Q-value

self.q_table[state][action] += self.alpha * (target_q - current_q)

# Training the agent

def train_agent(env, agent, episodes=100):

"""Train agent on the environment."""

rewards_history = []

steps_history = []

for episode in range(episodes):

obs = env.reset()

total_reward = 0

steps = 0

done = False

while not done:

# Choose action

action = agent.choose_action(obs)

# Take action

new_obs, reward, done = env.step(action)

# Learn from experience

agent.learn(

agent.get_state_key(obs),

action,

reward,

agent.get_state_key(new_obs),

done

)

obs = new_obs

total_reward += reward

steps += 1

# Limit steps to avoid infinite loops

if steps >= 100:

break

rewards_history.append(total_reward)

steps_history.append(steps)

# Print progress

if (episode + 1) % 10 == 0:

print(f"Episode {episode + 1}/{episodes}, Avg Reward: {np.mean(rewards_history[-10:]):.2f}, Avg Steps: {np.mean(steps_history[-10:]):.2f}")

return rewards_history, steps_history

# Set random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(42)

random.seed(42)

# Create environment and agent

env = GridWorldEnv(size=6, obstacle_prob=0.2)

agent = QLearningAgent(state_size=env.size, n_actions=len(env.actions), epsilon=0.2)

# Train agent

print("Training agent...")

rewards_history, steps_history = train_agent(env, agent, episodes=100)

# Plot training progress

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.plot(rewards_history, color='blue')

plt.title('Rewards per Episode')

plt.xlabel('Episode')

plt.ylabel('Total Reward')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.plot(steps_history, color='green')

plt.title('Steps per Episode')

plt.xlabel('Episode')

plt.ylabel('Steps to Goal')

plt.grid(alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/rl_training_progress.png')

plt.close()

# Visualize trained agent behavior

def visualize_policy(env, agent):

"""Visualize the learned policy."""

policy_grid = np.zeros((env.size, env.size), dtype=int)

arrows = ['→', '↓', '←', '↑']

# Reset environment

obs = env.reset()

# For each cell, choose best action

for i in range(env.size):

for j in range(env.size):

# Skip obstacles

if env.grid[i, j] == 1:

continue

# Move agent to this position

env.agent_pos = (i, j)

obs = env._get_observation()

# Get best action

action = agent.choose_action(obs)

policy_grid[i, j] = action

# Plot policy grid

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

env.render(ax)

# Add arrows indicating policy

for i in range(env.size):

for j in range(env.size):

if env.grid[i, j] != 1: # Skip obstacles

arrow = arrows[policy_grid[i, j]]

ax.text(j, i, arrow, ha='center', va='center', fontsize=20)

plt.savefig('images/blog/learning_paradigms/learned_policy.png')

plt.close()

return fig

# Test agent with exploration turned off

test_env = GridWorldEnv(size=6, obstacle_prob=0.2)

test_agent = agent

test_agent.epsilon = 0 # No exploration, just follow learned policy

# Visualize policy

policy_fig = visualize_policy(test_env, test_agent)

# Run a test episode

def run_test_episode(env, agent):

"""Run a test episode and return frames for animation."""

obs = env.reset()

done = False

frames = [env._get_observation().copy()]

while not done:

action = agent.choose_action(obs)

obs, _, done = env.step(action)

frames.append(env._get_observation().copy())

if len(frames) >= 30: # Limit steps

break

return frames

# Generate test episode frames

test_frames = run_test_episode(test_env, test_agent)

# Create animation

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 6))

colors = ['white', 'gray', 'blue', 'green']

cmap = ListedColormap(colors)

def update(frame):

ax.clear()

ax.imshow(frame, cmap=cmap, vmin=0, vmax=3)

ax.grid(which='major', axis='both', linestyle='-', color='k', linewidth=2)

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(-0.5, test_env.size, 1))

ax.set_yticks(np.arange(-0.5, test_env.size, 1))

ax.set_xticklabels([])

ax.set_yticklabels([])

ax.set_title('Agent Navigation Using Learned Policy')

return [ax]

# Save animation frames as individual images

for i, frame in enumerate(test_frames[:15]): # Limit to 15 frames for blog

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.imshow(frame, cmap=cmap, vmin=0, vmax=3)

plt.grid(which='major', axis='both', linestyle='-', color='k', linewidth=2)

plt.xticks(np.arange(-0.5, test_env.size, 1), [])

plt.yticks(np.arange(-0.5, test_env.size, 1), [])

plt.title(f'Navigation Step {i}')

plt.savefig(f'images/blog/learning_paradigms/navigation_step_{i}.png')

plt.close()

print("Visualization complete.")

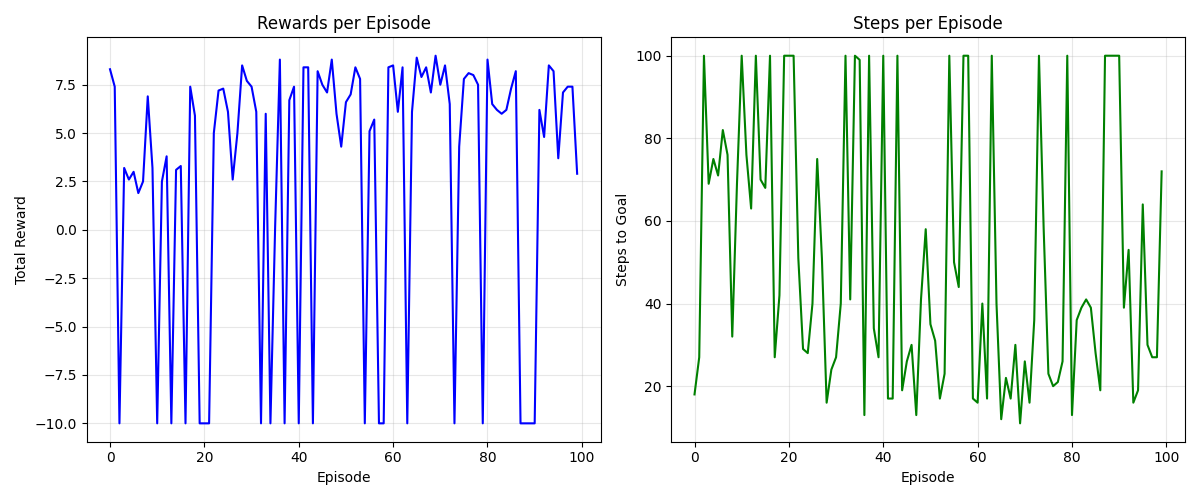

These charts show our agent's learning progress over time. On the left, we see the total reward per episode increasing as the agent learns a more efficient policy. On the right, we observe that the number of steps needed to reach the goal decreases, indicating that the agent is finding shorter paths.

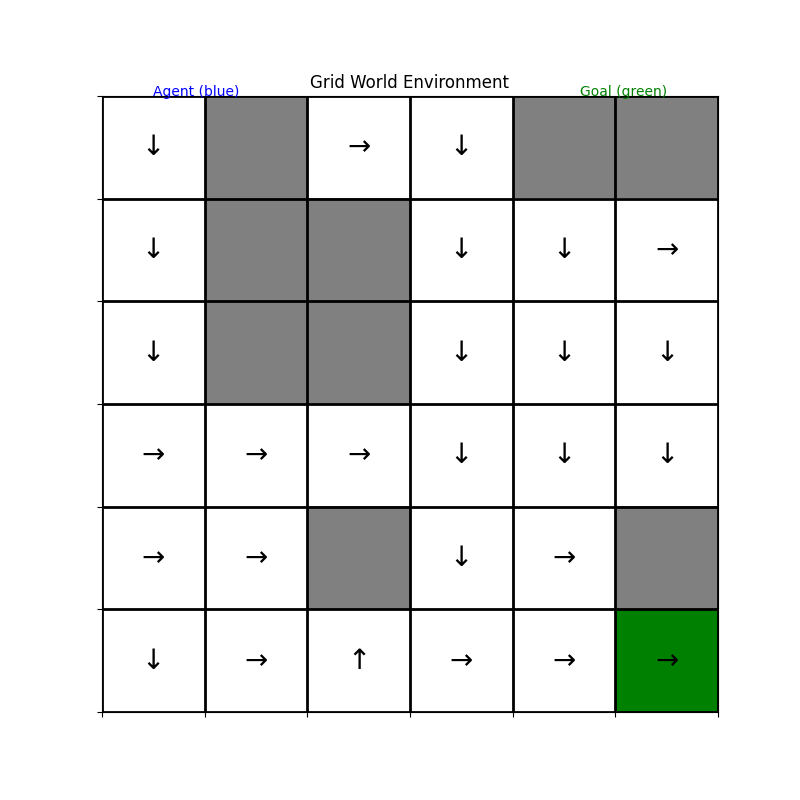

This visualization shows the policy our agent has learned after training. The arrows indicate which action the agent will take in each grid cell. Notice how the actions generally point toward the goal (in green) while navigating around obstacles (in gray). The agent has learned to make these navigation decisions purely from trial and error, receiving rewards for reaching the goal and small penalties for each step taken.

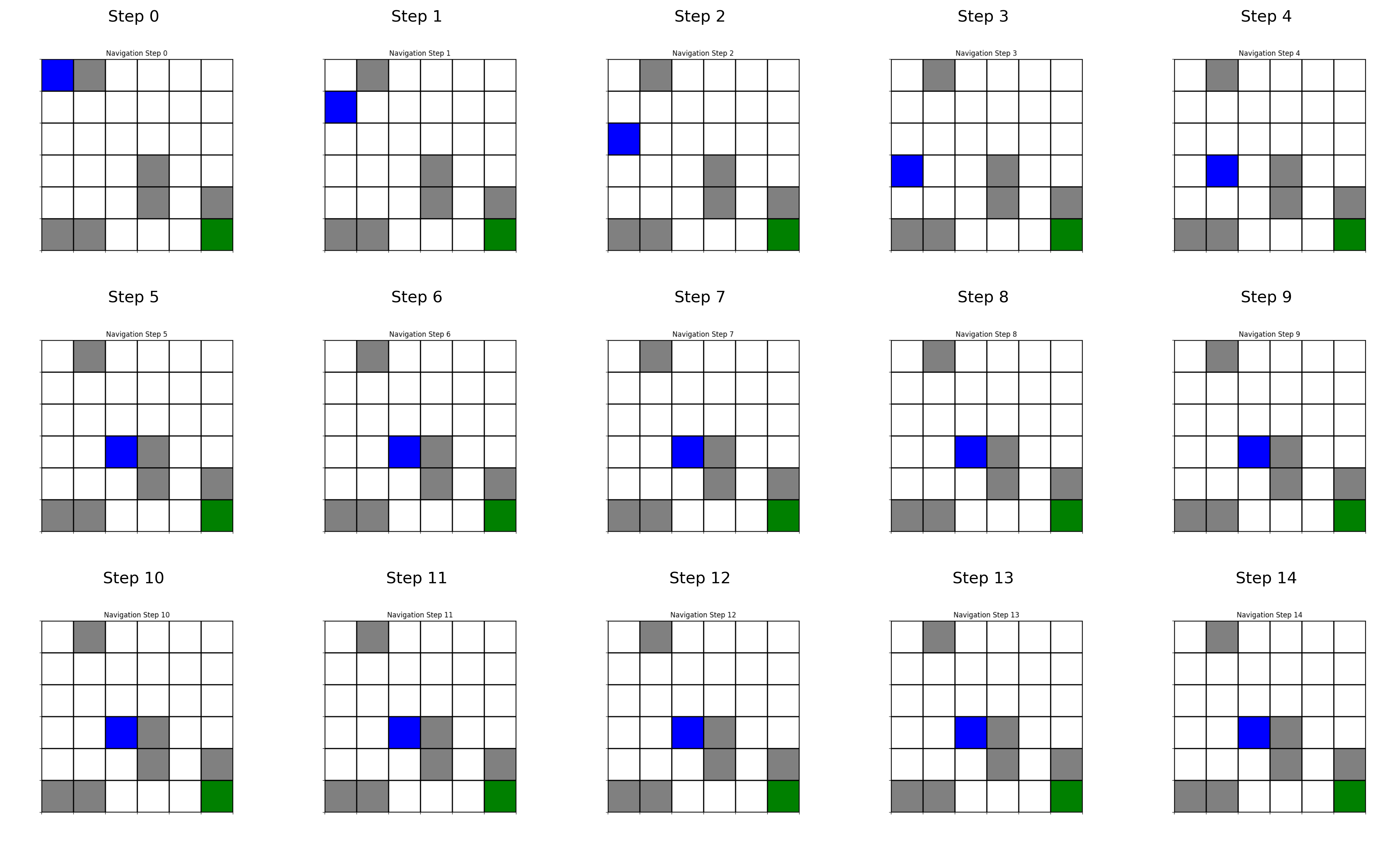

These snapshots from a test episode show the agent (blue) navigating from the start position to the goal (green), following its learned policy. The agent successfully avoids obstacles and finds an efficient path to the goal.

Visual Reinforcement Learning in Computer Vision

While our grid world example is simplified, reinforcement learning finds numerous applications in real-world computer vision:

-

Active Vision: RL agents learn where to look in an image to efficiently gather information or identify objects

-

Image Processing Pipelines: Optimizing sequences of image transformations for tasks like enhancement or restoration

-

Adaptive Compression: Learning compression strategies that adapt to image content

-

Visual Navigation: Robots and autonomous vehicles learning to navigate based on camera input

-

Interactive Visual Tasks: Learning to segment objects or track moving targets through sequential decision-making

The Power and Limitations of Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning offers unique advantages for visual tasks:

- Goal-directed learning: Optimizes toward specified objectives without explicit examples

- Sequential decision-making: Addresses tasks requiring multiple steps or adaptive strategies

- Online adaptation: Can adapt to changing environments and objectives

However, it also faces significant challenges:

- Sample inefficiency: Often requires many interactions to learn effective policies

- Reward specification: Designing reward functions that lead to desired behavior is difficult

- Exploration-exploitation trade-off: Balancing between trying new actions and exploiting known good ones

- Stability issues: Training can be unstable, especially with complex visual inputs

Combining Paradigms: The Future of Visual Learning

Our exploration has taken us across a spectrum of learning approaches, each with distinct strengths and limitations. In practice, the most powerful computer vision systems often combine multiple paradigms:

- Pre-training with self-supervision, followed by fine-tuning with supervision

- Using unsupervised clustering to generate pseudo-labels for semi-supervised learning

- Leveraging reinforcement learning on top of pre-trained visual representations

- Combining few-shot learning capabilities with large-scale pre-training

The boundaries between these paradigms continue to blur as researchers develop increasingly sophisticated hybrid approaches. This evolution mirrors our understanding of human visual learning, which also combines innate biases, self-directed exploration, explicit instruction, and goal-directed practice.

The Human Connection

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of these different learning paradigms is how they parallel human development:

- As infants, we learn largely through unsupervised observation of our visual world

- Children engage in extensive self-supervised learning through play and exploration

- Formal education introduces more supervised learning with explicit feedback

- Throughout life, we use reinforcement learning to refine our visual skills based on outcomes

This connection between machine and human learning not only helps us build better AI systems but also deepens our understanding of human cognition.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Learning Paradigm

As we conclude our journey through learning paradigms in computer vision, the key takeaway isn't which approach is "best," but rather which is most appropriate for a given context. Consider these factors when selecting a learning paradigm:

- Available data: How much labeled data do you have access to?

- Task complexity: What kind of visual understanding is required?

- Computational resources: What are your training and inference constraints?

- Adaptability needs: Will the system need to learn new concepts over time?

- Explainability requirements: How important is it to understand how decisions are made?

The future of computer vision lies not in the dominance of any single paradigm, but in their thoughtful combination—creating systems that can learn from explicit guidance when available while possessing the autonomy to explore, discover patterns, and adapt when guidance is sparse.

As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to transform how machines perceive and understand our visual world—bridging the gap between raw pixels and meaningful understanding, one paradigm at a time.